A recent opinion piece written by Liberia’s Presidential Press Secretary, Atty. Kula Bonah Nyei Fofana, has ignited national debate, reopening fault lines that touch Liberia’s deepest political, tribal, and religious sensitivities.

In her essay, titled “Releasing the Accelerator a Bit: The Fulani Security Saga,” Fofana identifies herself as “an active member of the Muslim community,” and asserts that her views are personal: “This is a personal opinion and does not reflect my office or portfolio.” Yet, the very fact that such a high-level government official felt compelled to defend what she describes as a misunderstood community volunteer corps has sparked anxiety about security, religion, and identity in a fragile democracy still haunted by civil war memories.

A Call for Calm Amid Fear

Fofana begins with a disclaimer: “I do not support any military or paramilitary organization whose purpose is to cause violence, intimidation, or destabilization in any form. The preservation of peace, national unity, and lawful order must remain paramount.”

Her intervention follows the viral circulation of a video showing a group calling itself the “National Fulani Security Organization.” Public outrage quickly flared, with allegations linking the group to militant or extremist motives. But Fofana urges restraint, warning that “before judgment, facts must come before fear.”

She argues that public concern about uniforms and coordination outside formal state security is understandable — but insists that the group’s intentions have been misread.

A Community Phenomenon, Not a Militia?

According to Fofana, the so-called Fulani security group is not new: “This organization did not emerge overnight… It has existed for years within the community and primarily operated during major Islamic gatherings.”

She cites multiple events, including Eid celebrations and the visits of international clerics like Mufti Menk and Sheikh Mohammed Awal, where the group worked side by side with national police to control crowds and maintain order.

Recalling her personal experience, Fofana writes: “From my own interaction and involvement in the community spanning over fifteen years through active community participation, engagements have consistently been cordial, respectful, and cooperative.”

In her view, these young volunteers are “ordinary people—students, traders, and workers—who come together during specific religious gatherings,” not agents of political or tribal mobilization.

The Real Issue: Appearance and Perception

For Fofana, the crisis is rooted not in the group’s function but in its public image. “The concern is less about what they do and more about how they appear,” she warns.

In her assessment, “Proper registration under national law, clear operational guidelines, coordination with state security agencies, training in non-violent crowd management, and possibly a name that reflects community service rather than force would address many fears.”

But she cautions against heavy-handed suppression: “Calling for immediate disbandment without engagement risks alienating young people who are already contributing to orderliness.” Her prescription? Guidance over condemnation.

Drawing Parallels with Christian Practices

In a move likely to stir both solidarity and controversy, Fofana compares the Fulani volunteers to Christian ushers and marshals often seen managing crowds at crusades, vigils, and church conventions. “The difference here appears not so much in the function but in the perception created by the name and structure,” she writes.

The comparison highlights Liberia’s delicate balance between faith communities — a country where religion, ethnicity, and political alignment can overlap in ways that easily inflame public sentiment.

A Test for the State

Fofana reframes the controversy as a “teaching moment” for the state: “Authorities such as the Ministry of Justice and law enforcement agencies should treat this as a teaching moment.”

Her proposal envisions supervision and legal integration instead of confrontation: “Providing legal framework, oversight, training, and integration into community policing initiatives can transform uncertainty into cooperation.”

To her, community service and volunteerism should not be criminalized if transparency and accountability accompany them.

Political Lines and Religious Realities

The timing of this debate, coming under a postwar administration still navigating fragile unity, cannot be ignored. Liberia’s peace depends not only on government oversight but also on keeping tribal and faith-based identities from becoming power blocs.

Fofana’s public identity as both a senior government officer and a Muslim leader complicates perceptions. Critics have accused her of defending a group tied to a specific ethnic community — the Fulani — whose transnational networks and cross-border movement have long triggered suspicion in West Africa.

Her choice of words — urging that we should not “throw the entire group/community under the bus simply to satisfy public outrage” — echoes that tension: it’s a call for fairness that, in today’s climate, can easily be read as partiality.

Ramadan as a Security Test

She reminds policymakers that Ramadan heightens public safety demands. “Late night gatherings, early morning prayers, and large congregations require coordination,” she writes. “Structured volunteer support under supervision enhances safety rather than undermines it.”

Here again, Fofana walks a fine line — validating the need for community assistance while implicitly challenging the state’s capacity to guarantee full coverage.

“Slowing the Accelerator” or Sounding Alarm Bells?

Fofana closes with an appeal for balance: “The question should not merely be whether they should exist, but how they should exist lawfully.” She adds, “Instead of applying full force on the accelerator through accusations and condemnation, we should slow down and steer toward regulation, partnership, and community safety.”

Her conclusion draws on the haunting words of Pastor Martin Niemöller’s Holocaust-era poem: “First they came for the socialists… Then they came for me.” It’s a moral warning about silence and collective fear.

Yet, political observers say her argument, though measured, exposes a troubling scenario: what begins as community service could, under poor oversight, evolve into armed ethnic solidarity. In a nation where war began with weaponized tribal mistrust, any informal “security” bearing ethnic or religious labels — however well-intentioned — poses a real threat to Liberia’s peace, trust, and national stability.

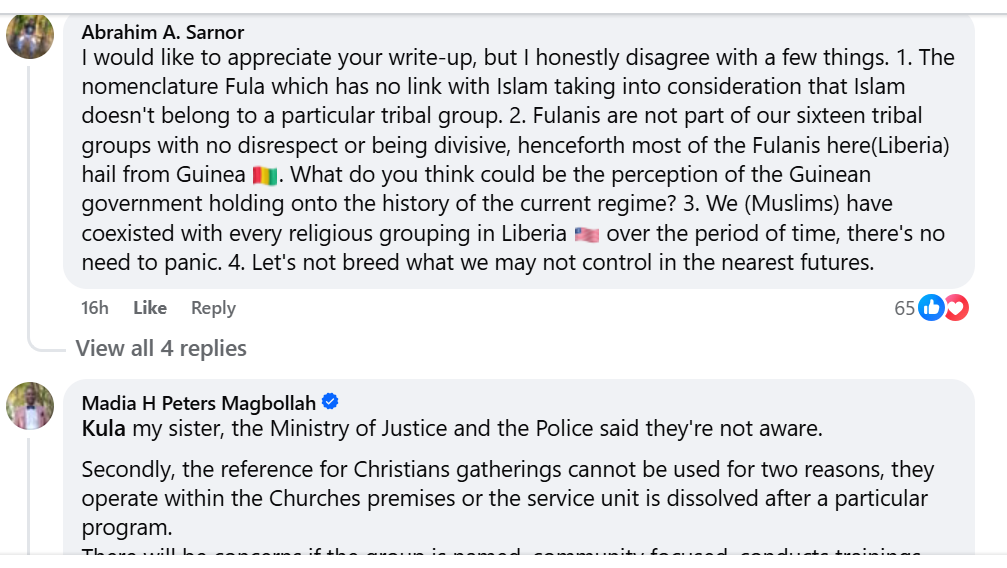

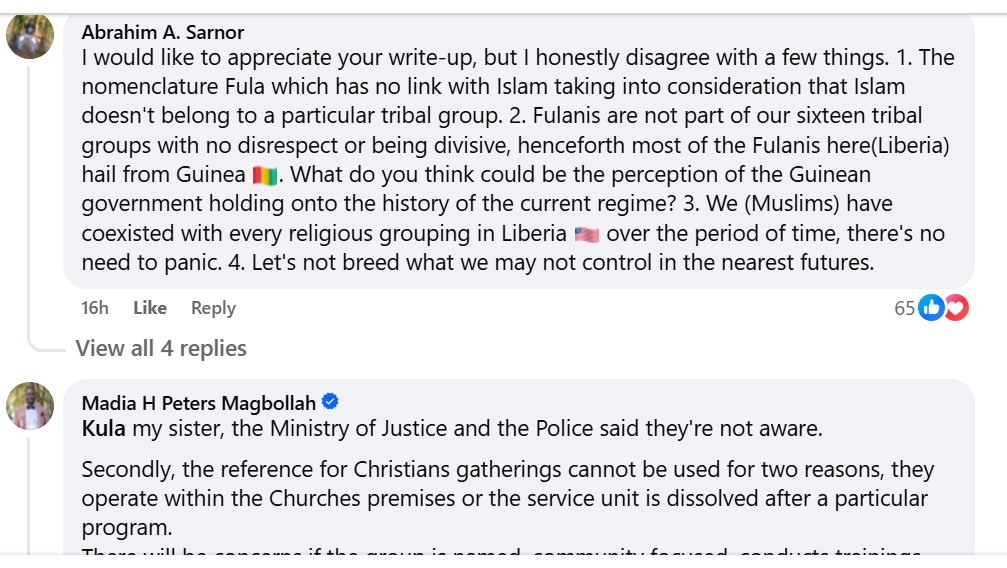

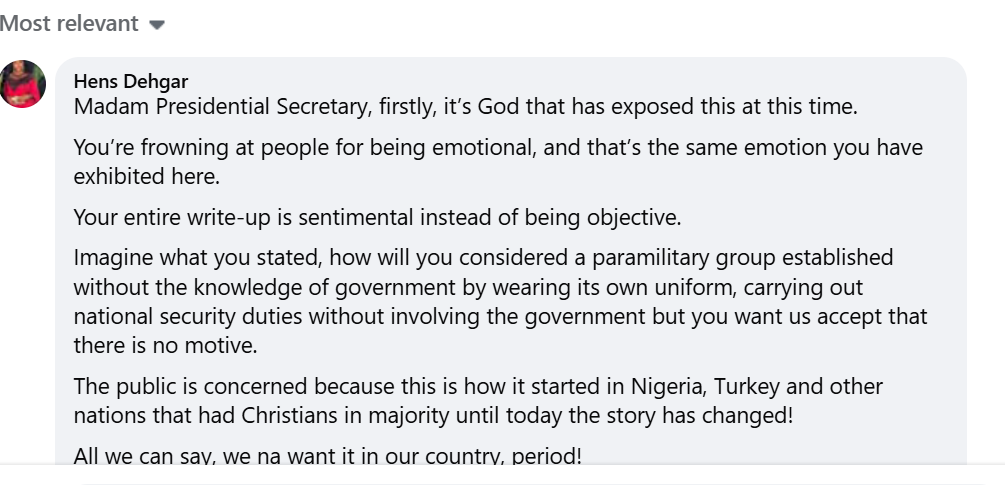

Public Reactions

Madam Presidential Secretary, firstly, it’s God that has exposed this at this time. You’re frowning at people for being emotional, and that’s the same emotion you have exhibited here. Your entire write-up is sentimental instead of being objective.

Edwin QuiQui Lombeh Jr.: “Kula’s piece is a rare mix of courage and balance. She refuses panic, insists on facts, and defends regulation over witch-hunt politics — this is the kind of leadership Liberia needs right now.

Prince Musa said : From a public-policy standpoint, a presidential press secretary cannot credibly separate personal opinion from official responsibility when commenting on the Presidency or on issues of the state—whether they affect public policy or private affairs—because the weight and influence of your voice flow directly from that office and its portfolio. Any public remark you make carries institutional authority and shapes perceptions of government posture. A “personal capacity” disclaimer does not neutralize that effect; it creates confusion, suggests internal discord, and risks undermining confidence in disciplined governance.

Example: “Speaking in my personal capacity, I believe the President’s recent comments on national priorities were misguided and should be reconsidered. This is my private opinion, not the official position of the Presidency.